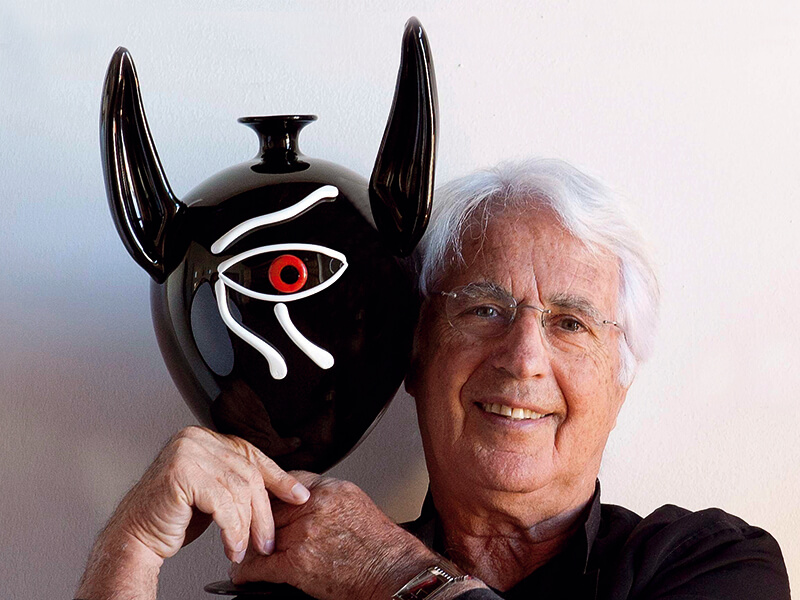

Interview with Cleto Munari | Editor of unique and timeless objects

Your artistic trajectory has always been multifaceted, leading you to perform different roles at the same time. Designer, entrepreneur, publisher, jeweller, artist: how do you like to define yourself?

At the moment, as a kind of editor. A dear friend of mine, Neri Pozza, editor for Mondadori, used to tell me: I am a publisher of books, you are a publisher of important objects. Now that’s how I like to call myself, a publisher always looking for my next bestseller.

Your debut in the world of design came relatively late, at forty years. What prompted you to take this path? What was it like to explore the world of design?

My activity in the world of design began around the age of 45, at a relatively late moment of my life which I still consider perfect today given the wide range of interests I had cultivated up to that moment. Horses, tennis, billiards, cards, women; in 25 years I hadn’t missed anything. At that point I began to feel the desire to marry and dedicate myself to something new, so I thought about the world of design. In fact, I had been passionate about this field for some time, especially graphics, so I thought it was a good idea to continue in that direction. Thinking about it afterwards, I can say that passion, resourcefulness and a bit of luck have guided me.

Do you remember a particular event that in your opinion marked your path in the world of design?

In 1970, the time when the Milan fair, the Fiera Campionaria, exhibited not only furniture, but everything related to the Italian production world, I found myself participating and winning the first prize as an emerging designer for a small carafe that I had designed on behalf of a company. The success of my attempt not only amazed me a lot, but convinced that somehow I could take that path. Even then I had the opportunity to meet some great designers of the time such as Gio Ponti, Marco Zanuso and Mario Bellini, but the most important meeting was certainly the one with Ettore Sottsass, of whom I became a great friend.

Finally in 1973 Carlo Scarpa moved to Vicenza. It happened that Ettore Sottsass was his great friend, so in a short time our common acquaintances led us to know each other and become friends. Without a doubt Carlo Scarpa was the man who marked a turning point in my life, changing me forever and guiding my every future step ever since. If it wasn’t for him I don’t know what I’d do now, the clochard probably * laughs *. He and Ettore Sottsass changed my life.

The meeting with Carlo Scarpa marked your destiny, both personal and professional. Tell us a little about your relationship. How much do you think it changed you knowing a genius like him?

Carlo Scarpa was, to say it in the Venetian dialect, “un ostia”; a particular and introverted person, aware and conscious of his abilities. He knew he was considered one of the greatest architects of the time not only in Italy, but all over the world. Frank Lloyd Wright admired him a lot and was totally reciprocated by Scarpa, so much that one can often see a great Wrightian influence in his architecture.

It was not easy to approach him because he was a naturally introverted and suspicious man. The first time I met him he greeted me barely and coldly. Fortunately, I was able to enter the good graces of his wife, who invited me to their house for dinner. From that evening in ’63 until ’78, I found myself visiting them every day, when the professor was there, from 9 am until 11 in the evening. On those occasions, we talked about art, design and contemporary architecture. If I could, I would accompany him wherever he went. His basic routine was dinners and breakfasts. He loved precious wines, champagne and caviar and wild strawberries very much.

What can you tell us about Ettore Sottsass. What kind of person was he and what relationship did you have?

I became friends with Sottsass even before with Carlo Scarpa. In those years Ettore often came to my house, about every other 15 days, because he loved and preferred the hospitality of people rather than the hotels. With him and Carlo Scarpa we organized some wonderful weekends, and also with Vittorio Gregotti, Roberto Sambonet and others. Each time there was gorgeous breakfasts and dinners. In my opinion, Sottsass was able to anticipate the world of design by 30 years, creating works in the 1960s that were appreciated later, in the 1990s.

Over time, internationally renowned designers have interspersed in the laboratory you created. What was it like living in that environment full of talents?

Thanks to Carlo Scarpa I was able to enter the world of design more and more over time, traveling among Denmark, Sweden, Finland and beyond to meet the greatest Scandinavian masters of the 1950s. It was around this time that I met Timo Sarpaneva, Alvar Aalto, Tapio Wirkkala and others.

I travelled to get to know them, and to discover what made them great. For my part, I had not only the passion, but also the pass of Carlo Scarpa whose fame and international admiration provided me a sort of passe-partout wherever I went.

Getting to know those people was a great source of inspiration for me, as well as a privileged way to understand more and more the world of design and make it mine. Through their eyes, I could understand what many others could not, the key to their art.

In addition to the names already mentioned, you have had the opportunity to work with many great Masters of the culture of the twentieth century, in the most disparate fields: architecture and design, but also art, literature, fashion… Can you tell us some encounters that has remained particularly in your heart?

In my life, I ranged from one part of the world to the other, travelling to immerse myself in many passions inherent not only to Design, but also Art, Architecture, Music and more. Every time I met incredible characters. I remember in 1986, during the exhibition organized for me by Hans Hollein in the Österreichische Galerie Belvedere in Vienna, I was lucky enough to meet Prince Schwarzenberg. He introduced me to the poet Václav Havel, a dissident of the communist regime at the time, with whom we spent the day. He told me then that if he ever returned to Prague one day, the first thing he would do would be to organize an exhibition dedicated to me. When Havel actually returned to the Czech Republic in 1992, where he was elected president, he proved to be a man of his word. He invited me to set up an exhibition in the Prague Castle.

Another particular personality was Nagib Mahfuz, Nobel Prize for Literature. He wanted to meet me after I dedicated to him one of my fountain pens. My wife and I flew to Egypt to spend time together.

In the many fields where you have distinguished yourself, object design is certainly one of the most remarkable. Your pieces are exhibited in museums around the world. Is there a particular project that you think has marked you more than others? And one that has determined your career as a designer?

I like to think that my career as a designer began a bit in the manner of the “serventini”. In Venice we have glass schools where young boys, called “serventini”, learn the craftmanship by observing the masters and helping them in their creative work. Here, I think I am just that. I have been the “serventino” of many masters, some more than others from whom I gradually learned the craft. Now that I have become a master glassmaker myself, I can blow pretty good things, carrying on my workshop of important objects; making poetry, as they say. I think the presence of our objects in over 100 museums around the world is a pretty good testimony to the fact that what we do is not that bad.

Among the projects that are most dear to me, I could mention the fountain pens that I have dedicated to some Nobel Prizes for Literature. The idea to dedicate special pens to noteworthy characters was born with Saul Bellow, American writer and Nobel Prize winner in 1976. I thought that if I managed to win him over, I would have an easy time with everyone else. Actually it went like this. When I visited other Nobel Prize winners saying that I had dedicated a pen to Saul Bellow, I always got a positive feedback. For the creation of these unique objects I turned to great designers such as Toyo Ito, Alessandro Mendini, Álvaro Siza Vieira and Oscar Tusquets Blanca. The result was five one-of-a-kind fountain pens dedicated to equally illustrious personalities such as Wole Soyinka, José Saramago, Saul Bellow, Nagib Mahfuz, and Toni Morrison. Saramago in particular was the most difficult to conquer. I was able to “corrupt” and win him only at the cost of great efforts.

One of your great intuitions was to bring great architects and designers to work in a world apparently far from their specialization, for example jewellery, creating collections hosted today in the most important museums in the world. How did this idea come about?

The idea of devoting myself to the creation of jewels was born around 1982 with the first two or three pieces created for my wife. Later I met Michele De Lucchi, whom I respect and believe is the greatest Italian architect in terms of sensitivity and quality of his works, with whom I was able to design another four to five pieces. From those first models, thanks to Ettore Sottsass and a group of American architects including Richard Meier and Michael Graves, the idea of starting a real business began to materialize. Today the production of jewellery is of crucial importance in our company along with rugs, furniture, writing instruments and other collectables.

Tell us about cutlery.

The idea of the cutlery was born after spilling a forkful of peas on my pants. * laughs *

At that time, families commonly used the San Marco forks, which in the 1700s, when they were created, also worked well, but having been remodelled over time, they had quite a few defects. One of them being the presence of only three tines. I proposed to Carlo Scarpa to design a more performing fork. At the time, we were in ’73, he ignored me, but we went back to talking about it in ’77 when, as he told me, the timing was right.

It was not uncommon for Carlo Scarpa to make this type of reasoning since, as he often said, to do some things it was necessary to have ideas, and not vice versa. He wasn’t a person you could say “do this to me” and he did it. It was the idea that guided him in his projects. In 1977 a new set of cutlery was born, an incredible mix of artisanship and design now housed in many museums around the world.

What is the role of the artisan in the creative process for you?

I believe that artisanship and ideas are a fundamental and completely independent part of the world of design. If there are no ideas, there is no design. Today, however, things are very different: Internet gives us the possibility to create anything in a very short time, giving life to everything in less than nothing.

You have lived as a protagonist in different eras of the world of design, with all their changes. What is your opinion on the aesthetics and trends that dominate today? Is there any young designer you particularly appreciate?

In my opinion, this is a somewhat sad moment in the history of design. Everything can be done immediately and with little effort, thanks to software and companies specialized in giving life to any type of project in short time. A great innovation, of course, which often however has the side effect of never being able to produce really new results or, better said, “innovative” in the strict sense.

Today there is not much, if any, of what Scarpa, Wright and Hoffman were doing. Not a case. In fact, it is not possible to create when the real inspiration is not the idea, but the time, the profit and the rush. For me the thought must proceed more slowly, accompanied – where possible – also by a good glass of wine and rest before seeing the light. That’s just how important ideas come out. Otherwise you risk giving life to something that seems new, but in fact, it is not really. If I look at a magazine for sofas today, it is impossible not to notice how much all the models seem the same, different only for some details and the signature at the bottom. There is a flattening of the choice.

Speaking of craftsmanship: what is the relationship with your Vicenza? You are a cosmopolitan figure with wide horizons and at the same time firmly anchored to the local reality. How do you manage to combine all this?

In reality I am from Vicenza by adoption. My true homeland is Friuli, and I spent my childhood in Vicenza because that was where my maternal grandparents lived. I love this city very much, although many might call it a bit too quiet. My wife, who is Neapolitan, has never really enjoyed herself here, but for me it has always represented a bond not only with my family, but also with my passions. Here we have iron and wood artisans, and Venice glassworks are always close by.

Travelling a lot, I got to know many other realities with which I established particular ties, Rome and Naples for example. The rhythm and warmth of those cities combine the passion for work with the possibility of creating more intimate relationships, made of kindness and friendships. Milan, on the other hand, has another flavour: more chaotic and troubled, the so-called “Milan to drink”, makes it difficult to get out of the loop, following more free patterns.

Do you have any future plans for you and your business?

At the moment, I expect to live up to 120. * laughs *

Even now that I am no longer a kid, I am dedicating myself to projects and ideas for the future of the company. Supported by my collaborators and especially by my nephew Alessandro, I am dedicating myself to novelties concerning carpets, jewels and other important objects that have always made our fortune. In short, I enjoy it.

Now the timetable is set on five-year plans, as others before me used to do. So I will meet you again in 2025, which I hope will be full of news and great ideas.

Courtesy of Maggiore Design – Galleria d’Arte Maggiore g.a.m., Bologna/Milano/Paris

Photo: Michele Sereni, Pesaro

Video: Archivio storico Istituto Luce, Cinegiornale “Radar”, presentazione del set di posate Scarpa-Munari, Venezia 1978